Pictou Casualties: The Second Battle of Ypres

For Canadians, the Second Battle of Ypres was the first major test of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The 1st Division saw battle at Neuve-Chapelle, with 100 casualties, and other battalions supported British combat, but Ypres was to provide a horrifying introduction to trench warfare on the Western Front.

The Second Battle of Ypres (the first fought in October, November 1914) consisted of several engagements beginning on April 22nd and lasting for several months, although the bulk of the fighting was in April and May. French, Algerian, Moroccan, Belgian, British, Indian, South African, New Zealand, Newfoundland, and Canadian troops faced an attack, supported with chlorine gas, by German forces around the Belgian town of Ypres. The German forces aimed to push back allied troops from the salient, or bulge, into their lines, thereby gaining the high ground. It was also a battle fought by the Germans to take attention from its main campaign on the Eastern Front. Ypres was the first successful large scale use of gas in the war, specifically chlorine, which caused blindness and damage to the lungs; leading to asphyxia or suffocation. By the end of the battle well over 100,000 men of all nations were dead or wounded and gas was to become a weapon used by both sides during the war.

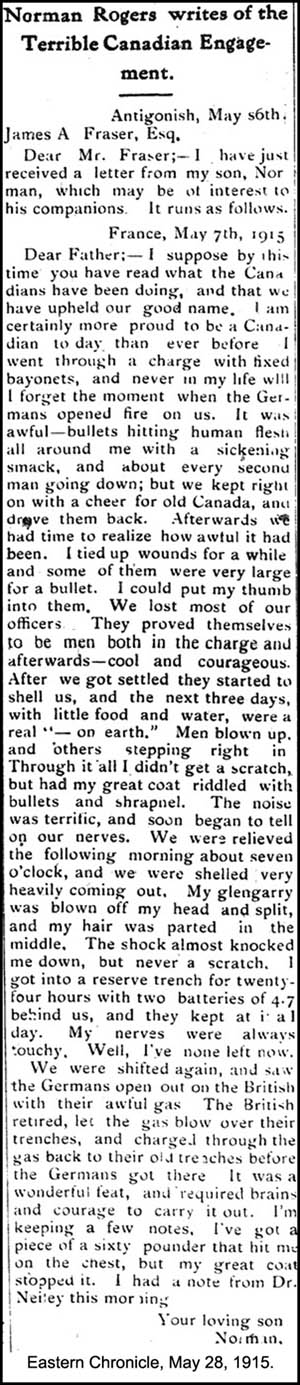

The 1st Canadian Division was engaged in the battle until relieved by British troops. Individual Canadian battalions continued to be engaged supporting British troops in the Ypres sector. Due to the surprise use of gas on the opening day of April 22nd the allied front along a 6 kilometre area collapsed. The Canadians were ordered to fill the gap and defend the allied flank. At Kitchener Wood the Germans were halted and repulsed by the Canadian Forces with heavy losses on both sides. The Germans attacked again on April 24th near St. Julien north of Ypres, using chlorine gas directly against the Canadians. The Canadians kept order despite the use of gas and bitter fighting took place with many casualties. In the end little territory was gained by the Germans but for the Canadians it proved to be an education in modern industrialized warfare, paid at a high price of 6035 casualties, including over 2000 dead. With the Second Battle of Ypres the Canadians developed a reputation as tough opponents and it began a transformation in how the commanders and soldiers saw themselves as a unified fighting force.

As reports came back to Pictou County through personal letters and newspaper reports, the realization that a major battle occurred took hold. As in all wars, confusion came first with rumours and reports of soldiers dead, wounded, and missing. As facts reached relatives back home the devastation was clear. Those who left New Glasgow as part of the 78th Pictou Highlander contingent, hoping to become part of a Nova Scotia Battalion, were instead sent to reinforce other battalions. Many joined the 13th and 15th Battalions who were in the thick of the fighting during Ypres. Four of those who left with the 78th were killed in action. Many other Pictonians were either injured or captured during the Second Battle of Ypres. It was a hard and savage introduction to the realities of a new method of warfare fought with tactics of a century before.

Private Angus Gray, son of Captain John Gray of Granton/Abercrombie, was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. At 34 years he was of medium height with light brown hair and blue eyes with a position as a chauffeur for James C. McGregor of New Glasgow before joining up. His brother Gunner George E. Gray joined shortly after and just arrived in France with the 23rd Battery, 3rd Brigade, Second Contingent. Angus was part of the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada) attempting to hold the line before St. Julian when he was killed on April 24th. His body was not found and he is remembered on the Ypres Memorial – Menin Gate.

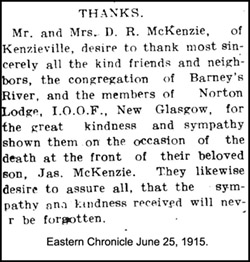

Private Adam James Mackenzie, son of Donald R. and Catherine MacKenzie from Barney’s River, was killed April 23rd as the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada) struggled to hold the left flank against gas, shells, and a concentrated German attack. It appears his body was not recovered until the 28th as many of the records list this as his date of death. He was identified by his army issued disc and had no effects to return. James, aged 39 and a clerk in civilian life, was described as 5 feet 9 ¾ inches with blue eyes and light brown hair. He declared himself a Roman Catholic upon enlistment. He is buried in Poelcapelle British Cemetery in Belgium.

Private Adam James Mackenzie, son of Donald R. and Catherine MacKenzie from Barney’s River, was killed April 23rd as the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada) struggled to hold the left flank against gas, shells, and a concentrated German attack. It appears his body was not recovered until the 28th as many of the records list this as his date of death. He was identified by his army issued disc and had no effects to return. James, aged 39 and a clerk in civilian life, was described as 5 feet 9 ¾ inches with blue eyes and light brown hair. He declared himself a Roman Catholic upon enlistment. He is buried in Poelcapelle British Cemetery in Belgium.

Private Cecil Richards was originally from Pugwash in Cumberland County, listing James Richards of the same town as next of kin. At the outbreak of war he was a 19 year old crane driver living in Stellarton. He was 5 feet 6 inches in height, of dark complexion with brown eyes, black hair, and a scar on his left calf. He declared himself a Baptist. As with Private Angus Gray he was with the 13th Battalion when he was killed on April 24th. Like many in the First World War Cecil’s body was never found as the size and number of artillery shells used obliterated the battlefield. He is remembered on the Ypres Memorial – Menin Gate.

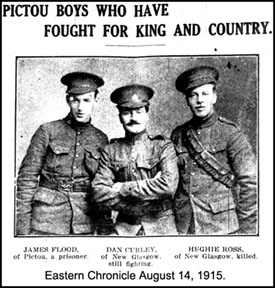

Private Hugh (or Hughie) Ross was 20 when he was killed on April 24th. His father was William Ross a well-known furniture dealer in New Glasgow. He was posted with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) but assigned to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade Signal Section for his final two months. In a letter to Hughie’s sister, Anna Ross, a fellow signaller and chum, Harry Adams from Saint John, New Brunswick described his death and how much he meant to the unit. He and Harry were loading and moving sandbags at the Brigade Headquarters in St. Julien when he was shot in the head, dying instantly. Harry had retrieved the envelope from Hughie’s pocket, which provided him an address to send his letter. Within two days the HQ was forced to retreat under intense German shelling. Hughie Ross’ body was never found and he is remembered on the Ypres Memorial – Menin Gate.

Private Hugh (or Hughie) Ross was 20 when he was killed on April 24th. His father was William Ross a well-known furniture dealer in New Glasgow. He was posted with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) but assigned to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Brigade Signal Section for his final two months. In a letter to Hughie’s sister, Anna Ross, a fellow signaller and chum, Harry Adams from Saint John, New Brunswick described his death and how much he meant to the unit. He and Harry were loading and moving sandbags at the Brigade Headquarters in St. Julien when he was shot in the head, dying instantly. Harry had retrieved the envelope from Hughie’s pocket, which provided him an address to send his letter. Within two days the HQ was forced to retreat under intense German shelling. Hughie Ross’ body was never found and he is remembered on the Ypres Memorial – Menin Gate.

It was following the Second Battle of Ypres that Canadian physician Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae wrote the famous war poem “In Flanders Field”. The poem holds some of the early romanticism of the War, which as the conflict dragged on and casualties mounted, turned to disillusionment for many. But even John McCrae has a Pictonian connection. He was close friends with Margaret MacDonald Matron-in-Chief of the Canadian Nursing Service from Bailey’s Brook, having served in the Boer War together.

Sources:

- Cameron, James M. “Pictonians in Arms”. University of New Brunswick and the author: Fredericton, NB, 1969. Available in library 971.613 CAM and online //novastory.ca/cdm/compoundobject/collection/picbooks/id/10244/rec/12

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission. “War Dead and Cemetery Records”. //www.cwgc.org

- Dancocks, Daniel G. “Welcome to Flanders Field”. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1988. Available in library 940.42 Dan.

- Cassar, George H. “Hell in Flanders Fields: Canadians at the second battle of Ypres”. Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2010. Available in library 940.42 Cas.

- “Eastern Chronicle. May, 1915 issues”. [Newspaper] Microfilm located in the New Glasgow Library.

- Greenfield, Nathan. “Baptism of fire: the second battle of Ypres and the forging of Canada, April 1915”. Toronto: HarperCollins, c2007.Available in library 940.42 Gre.

- Library and Archives Canada. “Soldiers of the First World War 1914-1918. Military Records”. //www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/first-world-war-1914-1918-cef/Pages/canadian-expeditionary-force.aspx

- Nicholson, G.W.L. “Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1915”. Queen’s Printer: Ottawa, 1962. //www.cmp-cpm.forces.gc.ca/dhh-dhp/his/docs/CEF_e.pdf

View a copy of this information sheet in PDF format.