|

|

|

|

|

Overview of Homarus americanus:

The American Lobster So what is a lobster do you ask? A mammal, a fish or some primitive sea creature? Well, in case you don’t know a lobster belongs to the category Invertebrata, one of the two categories making up the animal kingdom. Unlike us humans who belong to the other group, Vertebrata, invertebrates lack a vertebral column (a backbone). This is the classification system that all scientists use to categorize animals. Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. Below is the classification for Homarus americanus. Kingdom:

Anamilia Lobsters are actually closely related to insects! It’s hard to believe that these beady-eyed, clawed-clothed marine animals could be closely related to a mosquito or a grasshopper, but indeed they are. Lobsters, like insects, belong to the invertebrate phylum Arthropoda. Besides lobsters and insects, spiders and snails belong to this group as well. These animals are closely related because of two main characteristics that they share: they all have an exoskeleton (outer skeleton) and they all have joint appendages. Lobsters are farther categorized into the class Crustacea, along with other marine organisms like crabs and shrimp. These crustaceans are distinguishable from other Arthropods with hard exoskeletons, like mussels and clams, because their shell is softer and more flexible. Because lobsters have ten legs they belong to the order Decapoda (derived from the Latin word, ten feet). Also called the

American lobster, the Atlantic lobster or the true lobster, Homarus

americanus belongs to the family

Nephropidae. Another kind of

edible lobster found in the order Decapoda is the family

Palinuridae. These lobsters are called spiny lobsters or rock lobsters.

Unlike the American lobster they lack large claws, have spines all

over their bodies, and live in subtropical and tropical oceans.

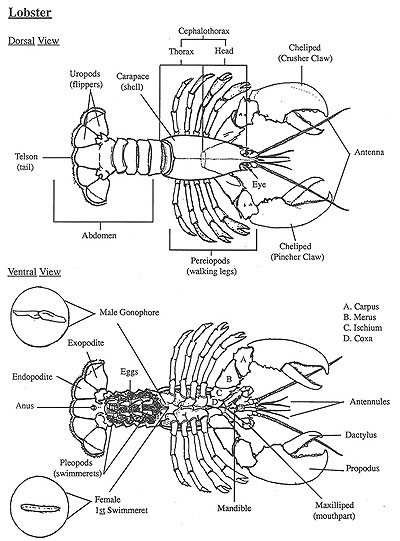

Anatomy and Biology of an Adult Lobster Like all Arthropods Homarus americanus, is bilateral. This means that if you were to cut a lobster from head to tail (or more correctly cephalon to abdomen!) right down the middle, you would come up with two equal halves. The organs are arranged in such a way that each half would be identical. (They would be mirror images of one another.)

Diagram courtesy of Department of Marine Resources, State of Maine. Body Plan: A lobster consists of two main parts. The first part, the cephalothorax, which is made up of the cephalon (the head) and the thorax (the mid-section), is often called the body of the lobster and is covered by a hard shell called the carapace. The second part that makes up the lobster is the abdomen, which is commonly called the tail. The 14 segments that are fused together to make up the cephalothorax are called somites and each somite bears a pair of appendages that are located on different areas of the lobster, usually on either side of the body or on the underside of the body. The eyes of the lobster are found on the first segment, and are housed at the end of two individual, movable stalks found on either side of the rostrum (the very tip of the cephalon). Each eye is actually made up of thousands of little lenses joined together, which is why they are called compound eyes. You would think that with all these “tiny eyes” that lobsters would have excellent vision, but ironically they do not. In fact, in bright light a lobster is practically blind. Lobsters cannot really see specific images but they can detect motion in dim light. The second segment of the cephalothorax bears the antennules, which are carried on a three-segmented peduncle (foot) and contain the chemosensory organs. The chemoreceptors found in these short antennae detect distant odors or chemical signals that are carried by the seawater. These messages received by the antennules help a lobster find food, choose a mate and decide if danger is near. The more then 400 different types of receptors found on the delicate hairs of the antennules are sensitive enough to allow a lobster to distinguish between particular species of mussels. Imagine having a nose that sensitive! The antennae, which consist of a five-segmented peduncle and a single flagellum, are located on the third segment. These antennae are much longer then the antennules and are used as sense organs as well.The last three segments of the cephalon and the first three segments of the thorax are where the mouthparts are located. The many mouths of the lobster have a variety of functions and are found on the underside of the lobster. Some are used to grip food such as the second and third maxillipeds. Others, such as the first and second maxillae and the first maxillipeds are used to pass this food along to the jaws, also called the mandibles, for crushing and ingestion. The Jaws are located on the fourth segment of the cephalothorax, and the other mouths are located on segments 5-9. The remaining segments of the cephalothorax are where one finds the walking legs of the lobster and what are commonly called the claws. These five legs (including the claws) are located on segments 10-14, and are joined to the lobster on either side of the body. The first three pairs of legs end in pincers, which are sharp, small, scissor-like claws that are used in handling and tasting food. Tiny hairs that line the inside of the pincers are sensitive to touch and taste. The first legs with the largest and sharpest pincers are called the claws. One claw is actually called the pincer claw, but the other is called the crusher claw. The crusher claw, being the larger of the two, is more powerful and is used to crush the shells of the lobster’s prey. The pincer claw is like a razor and is used to tear the soft flesh of the prey. Not only are humans right-handed or left-handed, surprisingly lobsters can be as well. Depending on whether its crusher claw is on the left side or right side of its body determines whether the lobster is left or right handed! The other two sets of legs that do not have pincers end in a point called a dactyl. These two sets of legs are mostly used for grooming and walking. At the base of the third walking legs in females the opening to the oviducts is located. This is the opening through which eggs are released. In males the opening of the sperm duct is located at the base of the fifth walking legs. The six segments that make up the abdomen are not fused together to allow for flexibility and movement. The soft tissue that connects them is not hard like the carapace. One of the advantages of having this flexibility is that it helps the lobster when it is in danger and needs to flee quickly. It’s tail is able to contract forcefully and then retract quickly, allowing the lobster to scoot backwards to safety. The first 5 segments of the abdomen bear the pleopods, which are also called swimmerets, and are located on the underside of the tail. The last segment, where the tail fan is located, is dived up in to a central telson with pairs of uropods on both sides. These uropods are pleopods that have been modified. Altogether there are five parts to the tail fan. Physiological processes and body systems: The digestive, excretory, respiratory, circulatory and reproductive systems of the lobster are located within the cephalothorax, below the carapace. These systems are quite similar to other species found in the order Decapoda. The digestive system of the American lobster consists of three stomachs, the foregut, midgut, and the hindgut. The first stomach, the foregut, contains a gastric mill, a set of grinding teeth that can grind food into fine particles. The particles then pass into the midgut glands where the particles are further digested. The midgut glands are actually the tomalley, the yummy green stuff that so many lobster lovers enjoy! Material that is too large to be absorbed is eventually passed into the hindgut and then through to the enlarged rectum and out the anus at the tip of the lobster’s tail. The excretory system removes toxic byproducts of protein metabolism and tissue breakdown. Wastes are eliminated via excretory organs located at the base of the lobster’s antennae. Urine is also released from this area through the nephropores. Wastes can also be eliminated through the gills, the digestive glands or can be lost when the lobster molts.Twenty pairs of gills located within the branchial chambers on either side of the cephalothorax are what comprise the respiratory system. These gills are made up of numerous feathery like filaments situated around a central rod and are protected within the gill chamber of the carapace. Water passes up through openings between the lobsters legs, over the gills and up towards the head. Every few minutes this current of water is reversed the other way so that debris can be flushed out of the chambers. An important part of this “gill current” is that when it is flowing forward towards the head it can project urine forward. It is thought that the urine of the lobster contains important information about the sex of the lobster, and it’s physiological state. A lobster does not have a complex circulatory system like we do. Instead of a four-chambered heart it has a single-chambered sac that consists of muscles and several openings called ostia. Their heart lies above the stomach on the upper surface of the animal (but still below the carapace of course!) A lobster’s circulatory system is known as an “open” system whereas our system is known as a closed system. The heart of an adult lobster beats 50-136 beats per minute. Coloring: Live lobsters are not red like the cooked ones you’ve bought at the store or restaurant. The colour of a live lobster does vary among individual lobsters, but most lobsters are either olive green or greenish brown. Orange, reddish, dark green or black speckles are commonly found adorning a live lobster and a bluish colour is often found at the joints of the lobster.

The major pigment in a lobster’s shell is

astaxanthin, which is bright red in its free state. In a live lobster

astaxanthin is chemically bound to proteins that change this colour to a

greenish or bluish colour. When

a lobster is boiled the heat from the water breaks the bonds that hold

this pigment to these proteins and the astaxanthin is released in to its

free state. Thus a cooked

lobster is bright red and not dark green. HabitatThe Northwest Atlantic is where the American lobster calls home. From Labrador to North Carolina this lobster is found eating, breeding and roaming the ocean floor. Lobsters prefer to make their homes in rocky areas where they can hide in the crevices from predators. However, young lobsters that have just settled on the bottom may not be able to find gravelly material so they burrow in pebble, sand or clay. In the first few years of a lobster’s life home is really where the hiding place is. A young lobster that has just settled on the bottom must hide away so as not to be eaten by predators, but older juveniles and adult lobsters that are larger and better equipped for protecting themselves can wander away from their burrows to explore. How far can these older lobsters actually travel? Studies done in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence in Atlantic Canada, have concluded that the 15,000 lobsters that had been tagged and released had moved an average of 10-15km from their release points. Similar studies done in other parts of Atlantic Canada have observed the same trends. With their large claws an adult lobster can dig away sand and gravel from under a rock, making a tunnel that they can call home. Some of the larger extensive burrows may house two or three lobsters of different sizes. Lobsters may be found from the low tide mark out to depths of approximately 400m. Although lobsters can be fished in deep waters, high concentrations are found closer to shore in shallower water, like in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence at depths ranging from 1-40 meters. Predators

and Diet

The biggest predator of the American lobster is man! After man, their next biggest predators are ground fish such as flounder and cod, sculpins, eels, rock gunnels, crabs, and seals. Lobsters are not fussy eaters. Although they prefer fresh food they will eat basically anything that they can get their claws on, even if it’s dead. (As is evident in their desire to get at the bait in the lobster traps!). The main diet of a lobster is crab, mussels, clams, starfish, sea urchins and various marine worms. They are also known to catch fast moving animals like shrimp, amphipods (also known as “sand fleas”) and even small fish. Lobsters eat mostly animals, but if these resources are scarce, as they are sometimes in the spring, a lobster might eat plants, or sponges to get energy. In the Northumberland Strait, an area making up a great part of the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence, a main dish for a lobster in the fall is a newly settled crab. Lobsters in this region can get up to 50% of their energy requirements from crabs. Some people believe that lobsters are cannibals.

This is really a misconception.

Lobsters have never been documented eating other lobsters in the

wild. This has only been seen

in close conditions with lobsters in captivity. It was once thought that

lobsters might be cannibals because scientists found traces of lobster

shells in the digestive systems of the lobsters they were examining.

However, it was later discovered that this material was actually

the lobster’s own shell that had been digested by it after it

molted.

A lobster may eat part of its old shell to absorb the calcium found

in it to strengthen their new shell that is forming |

||

|

|